In this prelab you will formulate some of the ideas necessary to complete Lab 05. Please type your solutions, and hand in a paper copy before the beginning of lecture on Wednesday. Remember, no late prelabs allowed!

Part 0 - List Practice

1. Write a chunk of code that creates a list containing the first 30 fibonacci numbers (1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, and so on). Don't use any variables other than the list itself, and an index variable (i.e. don't duplicate the code we developed earlier to compute the fibonacci numbers -- use the list!).

2. Write a chunk of code that prints the second largest integer in a list A of integers. You may assume A has already been declared and given values, and that all values are distinct. Don't use any Python list methods (like sort), and don't change the list. You should be able to find the second largest integer in a single pass through the list.

3. Write pseudocode for an algorithm that counts the number of pixels of every possible red value in a Picture. That is, the algorithm keeps track of how many pixels have a red value of 0, how many have a red value of 1, and so on, up to how many have a red value of 255.

Part 1 - Looking for a Match

As you may know, proteins are chains of molecules called amino acids. There are 20 amino acids, each of which is typically represented by a single letter, and any protein can be specified by its sequence of amino acids. This sequence determines the properties of the protein, including its 3D structure.

Right: 3D structure of a protein. Image source: wikipedia.org.

When a new protein is found, one way in which we might attempt to guess the functionality of that protein would be to see if it contains certain markers common to a known class of proteins. For example (and an entirely bogus example at that), suppose we discover a new protein, that we've named Duane, with the following amino acid sequence:

STTECQLKDNRAWTSLFIHTGHTECA

We may also suspect that Duane might belong to one of two possible classes of proteins: Splunkers and Munkatoos. As you well know, most Splunkers contain the pattern TECQRKMN or at least something close to it. That is, most of the sequences in the class of Splunker proteins have the subsequence TECQRKMN with only a few of the letters changed. Munkatoos, meanwhile, have the pattern ALFHHTTGT, or something very similar.

In this case, we can deduce that Duane is most likely a Splunker: Duane contains the pattern TECQLKDN which only has 2 mismatches from TECQRKMN (the errors are marked with a ^ below).

TECQLKDN

TECQRKMN

^ ^

The closest pattern to the Munkatoo sequence is

SLFIHTGHT ALFHHTTGT ^ ^ ^^

which has 4 mismatches.

Describe the Problem:

The problem you will be solving on your lab is as follows.

input: a file that contains a string s representing a protein sequence, along with some number of strings, each representing a marker sequence.

goal: for each marker sequence, find its best match in the protein sequence and report its location and the number of errors in the match.

Understand the Problem:

The file test.txt is in the format you should expect for your input. In particular, the first line will always contain the protein sequence. Following the protein sequence will be some number of marker sequences. For each of these sequences, you should report the location of the best match, and the number of errors at that location.

For example, the contents of test.txt are as follows:

STTECQLKDNRAWTSLFIHTGHTECA TECQRKMN ALFHHTTGT TTECQ HT ZZZ TTZZZRAWT

For this file your program should have something like the following output:

Example Output

Sequence 1 has 2 errors at position 2. Sequence 2 has 4 errors at position 14. Sequence 3 has 0 errors at position 1. Sequence 4 has 0 errors at position 18. Sequence 5 has 3 errors at position 0. Sequence 6 has 5 errors at position 5.

Design an Algorithm:

In order to solve this problem, you will need to figure out how to find the best match between a single marker sequence and the original protein sequence.

For example, if P contains the characters

STTECQLKDNRAWTSLFIHTGHTECA

ALFHHTTGT

Best match site: 14 Mismatches: 4since the best match occurs starting with the 14th element in P and has 4 mismatches, as discussed above.

4. Assume P is

STTECQLKDNRAWTSLFIHTGHTECAand S is GREWT. At which position does S have the best match, and how many errors does it have?

5. Write pseudocode for an algorithm that finds the best fit for a given subsequence to a given protein. Assume you have a String or (if you'd prefer) an list of characters P (representing the protein) and a shorter String or list of characters S (representing the marker subsequence). Your pseudocode algorithm should find the location at which to align the subsequence with the protein so as to minimize the number of mismatches. You should print both the starting index of the best alignment as well as the number of mismatches at that location. If there are multiple best alignments, use the earliest appearing one.

Part 2 - The Game of Life

The Game of Life, created by mathematician John Conway, is what is referred to as a cellular automaton. It is a set of rules rules which are used to generate patterns that evolve over time. Despite the name, the Game of Life is not a game; it is really a simulation. In some ways, it can be thought of as an extremely simplified biological simulator which produces unexpectedly complex behavior.

The Game of Life is played on an infinite board made up of square cells. It takes way too long to draw an infinite board, so we'll make do with a small finite piece. Each cell can be either live or dead. We'll indicate a live cell as a red square, and a dead cell as a black one. The board begins in some initial configuration, which just mean a setting of each cell to be either live or dead (generally we'll start mostly dead cells, and only a few live cells).

The board is repeatedly updated according to a set of rules, thereby generating a new configuration based on the previous configuration. Some dead cells will become live, some live cells will die, and some cells will be unchanged. This configuration is then updated according to those same rules, producing yet another configuration. This continues in a series of rounds indefinitely (or until you get bored of running your simulation).

Rules of Life

The rules are pretty simple: to figure out whether a cell (x,y) will be live or dead in the following round, you just look at the 8 neighbors of that cell (those that share a corner or an edge, so N, S, W, E, NW, NE, SW and SE). What happens to (x,y) next round depends on the number of its neighbors who are live and whether it is currently live or not. In particular:

- If a cell has 4 or more live neighbors, it dies (overcrowding).

- If a cell has 0 or 1 live neighbors, it dies (loneliness... *sniff*).

- If a cell has exactly 2 live neighbors, nothing changes (if it was live, it stays live, if it was dead, it stays dead).

- If a cell has exactly 3 live neighbors, it comes to life (I don't have a good explanation for this one, but it does seem to make for cool patterns).

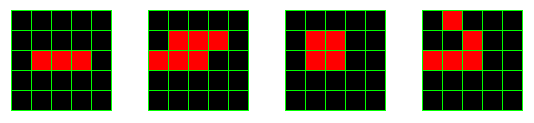

For example, consider the following 3 initial configurations, and the two configurations that follow each.

In the first example, both live cells have only one live neighbor, so they both die. Any dead cell has at most two live neighbors, so no new live cells spawn. Thus in one step, there are no live cells. Clearly, at this point, the configuration is stable.

In the second example, two live cells have only one neighbor, so both die. But the third cell lives, and the cell to its immediate left has exactly 3 live neighbors, so it spawns. On the next iteration, we find ourselves in a case similar to the previous example, and all cells die.

Note that we can't set a cell to be live or dead the instant we determine its status for the subsequent round; we will likely need to know whether it is alive or dead on this round to determine the future status of other nearby cells. To see this, consider the second example. We can immediately tell that the top-most live cell will die. But had we set it to dead immediately, then when we got to the second live cell, it would have only had 1 live neighbor and we would have (erroneously) determined that it too must die. Thus it is critical that we first determine for every cell whether or not it will be live, and only after doing so update the status of each.

In the last example, all currently living cells die; the middle cell has too many neighbors, and the other have too few. However, four dead cells have exactly 3 live neighbors, and so those cells spawn. In the following round, there are neither cells that die nor cells that spawn, so we have a stable configuration. In general, a pattern that doesn't change is called a still-life.

While all of these patterns stabilized quickly, some patterns take a long time to stabilize, and some never do. Of those that never stabilize, some at least have a regularity to them; they eventually eventually repeat states. These are said to be oscillators. Others never repeat the same state again, and produce an infinite number of configurations.

Describe the Problem:

The problem you will solve on your lab is as follows.

input: none (although we may may change this later so that there is some way to input an initial configuration)

goal: simulate the game of life on an initial configuration that is hard-coded into your program.

Understand the problem:

Consider the following four intial configurations.

For each of these, you should specify the next four generations of each. You can either draw pictures, or type solutions. If you do the latter, I suggest you use a fixed width-font (like courier) and use a period (.) for a dead cell, and an X for a live cell. For example, the initial configurations would look like:

..... ..... ..... .X... ..... .XXX. .XX.. ..X.. .XXX. XXX.. .XX.. XXX.. ..... ..... ..... ..... ..... ..... ..... .....

7. Specify the next 4 generations of configuration B.

8. Specify the next 4 generations of configuration C.

9. Specify the next 4 generations of configuration D.

Design an Algorithm:

Let's think about how we might go about setting up our Life simulator. Since this program is relatively complex, we won't try to get everything working at once. For example, we won't do anything graphically until the logic of the simulation is working.

So what components do we need to run our simulation? First, we'll want to keep track of our current board: which cells are alive, and which aren't. We'll encode these with a 2-dimensional table of integers (a list of lists), called board, using 1 to represent live cells and 0 to represent dead cells.

Now let's think about how to perform a single update to board. At a high level, we simply want to update every cell in board. But remember, we'll run into problems if we update one cell and then update the cell next to it, since each update needs to be done as if none of the others have been done. To solve this, we'll do our updates on a new board, cleverly called newBoard, based on -- but without changing -- the original board. Now we can view our overall strategy as follows:

- Declare and initialize board and newBoard.

- Assign board whatever starting configuration you'd like.

- Update each cell in newBoard according to the rules of Life, referring to board to count the number of live neighbors for any given cell.

- Swap board and newBoard so the process can be repeated.

- Print the contents of board.

This list immediately suggests a few functions that will be useful to create: a function to print the board in a manner as suggested on the prelab so we can see if things are working; a function that creates a board of zeroes of a given width and height; a function that counts the number of live cells neighboring a particular cell in an array; and finally, a function that uses the previous function to update a board.

As we saw in class, we can make a two dimensional array -- a list of lists -- with all values initialized to 0 as follows:

a = []

for i in range(w) :

a.append([0]*h)

Something like

a = [[0]*h]*wdoesn't give us what we want? Why not? Hint: what happens when we change a single entry in this table?

The edges of the board tend to be problematic. For example, if you are considering cell (WIDTH-1,HEIGHT-1) and you attempt to check the liveness of its neighbors as you would for most cells, you'll end up attempting to access positions whose indices are too large. You may have run into this problem in the previous lab doing operations such as blur.

One natural fix is to simply create a board that is 2 units taller and 2 units wider than you actually want, and only do updates on non-border cells. This approach would work fine, but on this lab you're going to do something a bit different; we're going to use a torus rather than a plane for our game board. A torus is just the technical name for the shape of a donut.

OK, so what does that mean here? It means that if you were to walk off the right side of the board, you'd appear on the left side at the corresponding position, and vice-versa. Likewise if you walked off the top of the board, you'd appear on the bottom. This means every cell has 8 neighbors now. Consider cell (0,0). It has the 3 obvious neighbors in the directions E, SE and S. If we want to find the N neighbor, we have to wrap around the top of the board, bringing us to (0, h-1). Similarly, the NE neighbor would be (1, h-1). The NW neighbor would be (w-1, h-1), and so on. One reason this is so handy is that if you use the mod operator appropriately, you don't need any special cases to handle edges or corners.

Alright, so what did this have to do with donuts? Well, since the top of the board is now effectively connected to the bottom of the board, you could imagine the board as a flexible square of rubber, and this connection could be represented by gluing the top edge to the bottom edge. Now we've created a rubber tube. But the left and right edges are also connected. If we bend our tube and glue these edges together, we've created a torus. Mmmm... donuts.

10. Write psuedocode to go through a single iteration of the game, and update all of the cells on the board.

Honor Code

If you followed the Honor Code in this assignment, write the following sentence attesting to the fact at the top of your homework.

I affirm that I have adhered to the Honor Code in this assignment.